|

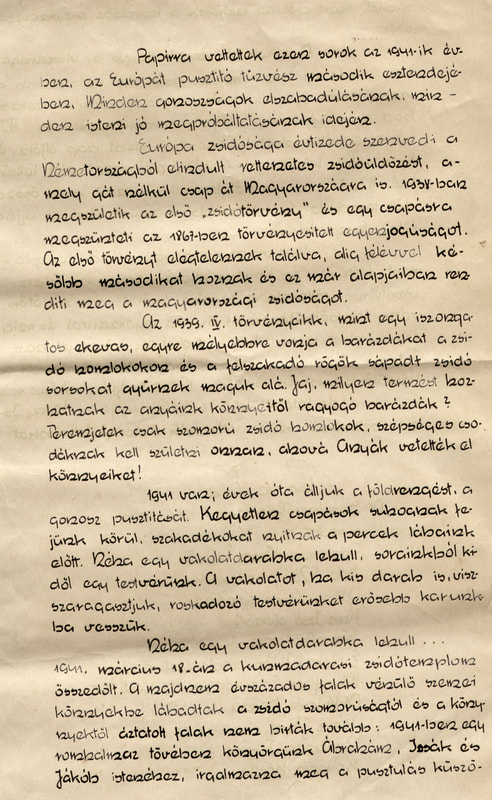

Papírra vettettek ezen sorok az 1941–ik évben, az Európát pusztító tűzvész második esztendejében. Minden gonoszságok elszabadulásának, minden isteni jó megpróbáltatásának idején. Európa zsidósága évtizede szenvedi a Németországból elindult rettenetes zsidóüldözést, amely gát nélkül csap át Magyarországra is. 1938–ban megszületik az első zsidótörvény és egy csapásra megszűnteti az 1867–ben törvényesített egyenjogúságot. Az első törvényt elégtelennek találva, alig félévvel később másodikat hoznak és ez már alapjaiban rendíti meg a magyarországi zsidóságot. Az 1939. IV törvénycikk, mint egy iszonyatos ekevas, egyre mélyebbre vonja a barázdákat a zsidó homlokokon és a felszakadó rögök sápadt zsidó sorsokat gyűrnek maguk alá. Jaj, milyen termést hozhatnak az anyáink könnyeitől ragyogó barázdák? Teremjetek csak szomorú zsidó homlokok, szépséges csodáknak kell születni onnan, ahová Anyák vettették el könnyeiket! 1941 van, évek óta álljuk a földrengést, a gonosz pusztítást. Kegyetlen csapások suhognak fejünk körül, szakadékokat nyitnak a percek lábaink előtt. Néha egy vakolatdarabka lehull, sorainkból kidől egy testvérünk. A vakolatot, ha kis darab is, visszaragasztjuk, roskadozó testvérüket erősebb karunkba vesszük. Néha egy vakolatdarabka lehull… 1941. március 18–án a kunmadarasi zsidótemplom összedőlt. A majdnem évszázados falak vénülő szemei könnybe lábadtak a zsidó szomorúságtól és a könnyektől áztatott falak nem bírták tovább: 1941–ben egy romhalmaz tövében könyörgünk Ábrahám, Izsák és Jákob istenéhez, irgalmazna meg a pusztulás küszöbén… Őseink istene meghallgatja a mi könyörgésünket, mert erőt ad nekünk a harchoz a gonoszság ellen. A vakolatot, ha kis darab is, visszaragasztjuk… A mi templomunk csak kis mészdarab a nagy zsidó szentély falán, de a szentélyből nem szabad elpusztulnia még oly kis darabkának sem. Mikorra a mi vétkeinket kiengesztelő szent nap eljön, új, tiszta falak között tartjuk Isten elé megtisztult lelkünket. Mert épségben él bennünk most is az összedőlt templom és mi tovább akarunk élni az újjáépített templomban. 1941 van, madarasi zsidók templomot építünk az Úristen dicsőségére...

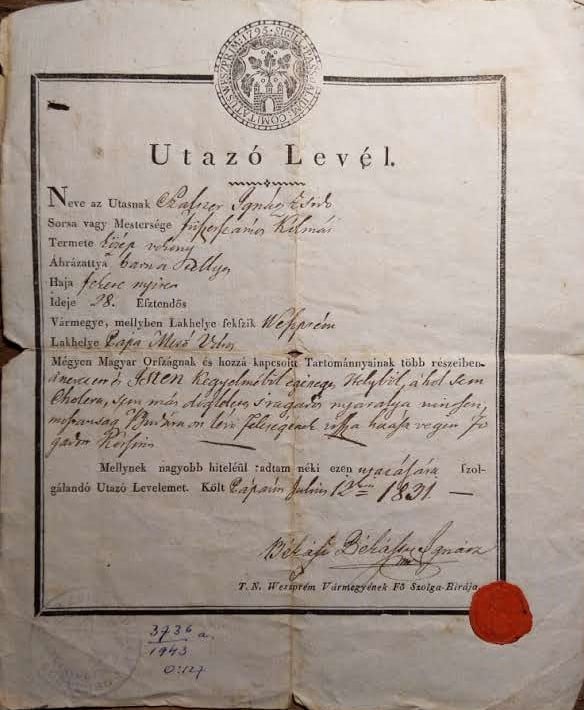

„Gábor Marianne — alkata szerint — boldogságra termett. Közönségében azt tudatosítja, hogy mindenek ellenére élni jó, mert a szem érdekes, vidám, nagyszerű, mulatságos, tanulságos, nemes dolgok befogadására teszi alkalmassá az embert.” (Pogány Ö. Gábor) Ha a XIX. század végén és a XX. elején született, majd az első világháborúig tartó sikeres asszimilációban részt vevő zsidó nagypolgárság történetét egyetlen család történetébe szeretnénk belesűríteni, aligha választhatnánk jellemzőbbet, mint Gábor Marianne (1917-2014) festőművészét. Szülei egész életükben – sok más tehetős zsidó családhoz hasonlóan –munkájukkal és mecénási tevékenységükkel nagyban hozzájárultak a magyar kultúra gondozáshoz, terjesztéséhez, a hátrányos helyzetűek támogatásához, neveltetéséhez. Gábor Marianne 1917. április 26-án született Budapesten, és itt élt egész életében. (A Centropa részletes életrajz-interjút készített a művésszel, a csaknem 60 oldalas interjú egy hihetetlenül érdekes, tartalmas és sok hasonló családhoz hasonlóan tragikus eseményekkel teli élet eseményeiről olvashatunk.) Apai nagyapja Léderer Gábor (Gábriel) rabbi, nagyanyja: Klein Lotti. Három fiuk született, a legidősebb Gábor Marianne apja: Léderer Ignác (1868–1945). Anyai nagyanyja, Rubin Anna szerb zsidó családból származott, akik Szerbiából menekültek el. Anyai nagyapja, Raiss Móric bőrgyárigazgató volt. Anyai nagyszüleinek nyolc gyermeke volt. Gábor Marianne édesanyja volt a legidősebb, Raiss Izabella Lucia (1880–1944). Szülei 1900 novemberében házasodtak össze. Édesapja 1921-ben Bardócon (Baldovce, Baldovskákúpele, Szepes vm.) gyermeküdültetésbe kezdett. Felmenői a magyarországi zsidóság kiválóságai voltak: családfája apai ágon a sátoraljaújhelyi Teitelbaum Mózesig, a Jiszmách Mose című rabbinikus munka szerzőjéig, anyai ágon Tyroler Ignác rézmetszőig, a Kossuth-bankók készítőjéig vezethető vissza. Nagyapja rabbi volt, édesapja, Gábor Ignác nemzetközileg elismert tudós, a magyar verstan egyik legkiválóbb kutatója. Ő volt az óizlandi-germán Edda-dalok magyar fordítója is, a Vándordiák-mozgalom megalapítója, 1911-től a zsidótörvényék tiltásáig az általa alapított, Munkácsy Mihály utcai híres Fiúnevelő Intézet megalapítója, igazgatója. Marianne bátyja, György több könyv szerzője volt. S nem feledkezhetünk meg természetesen Gábor Marianne férjéről, a nagyszerű költőről-műfordító-irodalomtörténészről, Rónai Mihály Andrásról sem. A családi krónika vége tragikus: a tudós Gábor Ignácot, a magyar nyelv és irodalom szerelmesét, aki mellesleg rendkívüli módon hasonlított Móricz Zsigmondra, hetvenhét évesen elhurcolták a nyilasok, és 1945. január 10-én a Liszt Ferenc téren a gettóba kísérés helyett – vejének, Rónai Mihály Andrásnak az egész családjával együtt – agyonlőtték. Feleségét, Raiss Izabellát, magyar írók német nyelvű tolmácsolóját, már két hónappal korábban Gönyűnél a Dunába lőtték. Szüleinek meggyilkolásáról, édesapja tömegsírjának exhumálásáról megdöbbentő részleteket olvashatunk a Centropa-interjúban. Gábor Marianne 1944 áprilisában – a legvészterhesebb napokban, alig több, mint egy hónappal a német megszállás után – férjhez ment Rónai Mihály András (1913–1992) költő-irodalmárhoz, aki ekkor munkaszolgálatos volt, ahonnan három nap eltávozást kapott. A házasság egy életre szóló, lelki és szellemi közösség volt.. Gábor Marianne saját emlékei szerint már ötéves kora óta rajzolt, édesapjáról ekkor készült portréja ma is megvan. Ebben az időben írt hozzá verset a család jó barátja Heltai Jenő, Marianne emlékkönyvébe címmel, amelynek híres első sora így szól: Akit az istenek szeretnek, Örökre meghagyják gyereknek. (https://moly.hu/konyvek/s-nagy-katalin-gabor) Nyolc-kilenc éves korában készült emberábrázolásaira Kernstok Károly figyelt fel, s mikor tizennégy éves lett, Szőnyi István festőiskolájára küldte. Tanulmányait ott, majd a gimnáziumi érettségi után Réti István és Szőnyi István növendékeként a budapesti Képzőművészeti Főiskolán végezte, ahol 1939-ben Nemes Marcell-díjjal tüntették ki. Főiskolás korában, 1938-as Tavaszi Szalonon mutatta be Örkényi-Strasser István unszolására beküldött első két képét a nyilvánosságnak a Szinyei Társaság, amelynek tárlatain 1941-ben Hatvany-díjat, 1940-ben és 1942-ben Kitüntető Elismerést nyert. Ettől fogva szerepelt mind a KÚT, mind a Nemzeti Szalon kiállításain (az utóbbinak már tagjaként), valamint a nemzeti kiállításokon is (az 1939-es nemzeti kiállításon egyetlen főiskolás festőként). 1936-ban és 1938-ban néhány hetes utat tett Velencébe és Padovába. Szőnyi István olaszországi ösztöndíjra terjesztette fel, de ezt a magyar kormányzat elutasította, a francia kormány által felajánlott ösztöndíjat pedig az időközben kitört háború miatt nem vehette igénybe. Első önálló kiállítására 1942-ben került sor; 1941 és 1943 között minden évben, Szőnyi Istvánnal, Berény Róberttel, Vass Elemérrel, Szobotka Imrével, Vörös Gézával egy időben Zebegényben dolgozott. Első önarcképét 1944 januárjában, akkori második önálló kiállításán szerezte meg a Fővárosi Képtár. Már a felszabadulás másnapján részt vett a képzőművészek szabad szervezete és az akkori Rippl-Rónai Társaság alapításában. Műveivel ott volt az Első Szabad Nemzeti Kiállításon. Az Újjáépítési Díjat –legfiatalabbként s egyetlen női művészként nyerte el, 1947-ben pedig máris új önálló kiállítással jelentkezett. Pályája negyedik önálló kiállítását 1948-ban a Margit-híd újjáépítésének ábrázolásának szentelte. Az 1945-től 1948 végéig terjedő időszak valamennyi nemzeti kiállításán s a Fővárosi Képtár, a Műcsarnok, az Ernst Múzeum stb. összes tárlatain részt vett. 1948 augusztusától december végéig olaszországi és franciaországi tanulmányutat tett. A fordulat éve után, 1949 elejétől – „polgári” származása miatt – nem állíthatott ki, kapcsolata közönséggel és művészeti élettel 1955 második feléig teljesen szünetelt. Pályája 1957. március 2-án megnyílt nagyszabású kiállításával indult újra. 1957-58-ban Franciaországban és Olaszországban töltött fél esztendőt, 1958-ban Londonban és Belgiumban járt. 1958-ban a brüsszeli világkiállítás magyar napján, Antwerpenben rendezett bemutatóján szerepeltek képei. Az ezután következő néhány évben művei a magyar művészetet reprezentáló kiállításokon Berlinben, Oslóban, Kijevben, Tallinnban, Prágában, Varsóban, Teheránban, Bagdadban, Új-Delhiben, Kuvaitban vettek részt. Másutt – mint a bordeaux-i, illetve mérignac-i biennálén való részvételekor – egyéni meghívásoknak tett eleget. Ezekben az években művei Magyarországon is számos reprezentatív tárlaton vettek részt, köztük a Magyar Képzőművészeti Kiállítások legtöbbjén. Bejárta Európa legtöbb országát, huzamosabban mindenkor Olaszországban és Franciaországban időzve, s minden alkalommal — mint azelőtt is mindig — a maga erejéből vagy külföldi meghívásra. Számtalan önálló külföldi kiállítása volt a hatvanas évek közepétől kezdve. Ezek mindegyikét a művészt meghívó ottani vezető galériák és városok rendezték. Carlo Levi és Renato Guttuso javaslatára Velencében már 1958-ban beválasztották a Société Européenne de Culture-be, ahol másodmagával, Bernáth Auréllal foglalt magyar festőként helyet; ottani második kiállítása alkalmával Giorgio de Chirico osztotta meg vele saját évenkénti tárlatainak termeit. Munkái – a Magyar Nemzeti Galériában őrzött harminc műve és más hazai múzeumok, intézmények, valamint gyűjtők tulajdonában lévő képei mellett – nagy számban kerültek külföldi múzeumokba, köz- és magángyűjteményekbe. „Léleklátó és lírai” portréfestészetét dicsérték a kritikusok az 1966–1967-es római művészeti szezont megnyitó kiállítását méltatva. 1976 novemberében került sor önálló külföldi kiállítására Firenze városának meghívására és rendezésében, a Fra Angelico műveinek múzeumául szolgáló San Marco kolostor középkori kerengőjében és termeiben, amelynek alkalmával Leonardo-éremmel tüntették ki. Egyszerre két önarcképe erről a kiállításról került az Uffizi-képtárba. Azok közül, akik pályáján elindították s bátorították, elsősorban mesterének, Szőnyi Istvánnak, valamint Kernstok Károlynak, Berény Róbertnek, Herman Lipótnak, Elekfy Jenőnek és Petrovics Eleknek mondott köszönetet. Kegyelettel gondolt anyai nagybátyjára, a jeles Székely Bertalan-tanítvány Teplánszky Sándorra is, akinek épp az övétől eltérő látásmódja ösztönözte arra, hogy csakis saját látásának engedelmeskedjék. Az 1977 végén – a Magyar Nemzeti Galériában – megnyílt nagyszabású kiállítását szülei emlékének ajánlotta. Művészi pályája a nyolcvanas évek végétől a szakmai figyelem – a több évtizedes tiltás, tűrés után – szükségszerűen az avantgárdok, a modernek (főleg a konstruktívok és absztraktok) felé fordult. Átrendeződtek a képzőművészeti intézmények, megjelentek a magángalériák. A kilencvenes években Gábor Marianne határozottan elutasította a piac érdeklődését, nem akart eladni a képeiből, ezért a műkedvelő közönség nem találkozhatott a festményeivel. A Jászi Galéria 2012-ben – még a művész közreműködésével – rendezte első kiállítását. A híres 1977 -es MNG kiállítástól haláláig eltelt 37 évben arányosan nőtt a művek száma. Gábor Marianne haláláig folyamatosan dolgozott. „…őszinte odaadással beszélek Gábor Marianne tájképeiről, …, hegedűjéről levette a hangfogót, szabadon zengenek a húrok, illetve a színek felszabadították magukat. Az az érzékeny idegesség, hevült lelkiállapot, ami Gábor Marianne-ra, az emberre jellemző, belekerült képeibe is, ezért olyan mozgalmasak vonalban, el nem határoltak formában, csengően világosak, egyértelműek színben.” Kassák Lajos 1957 Farkas Zsófia 1831 július 12-én a pápai Szalczer Ignácz 28 éves vékony termetű fűszerkereskedő zsidó útlevelet kért, hogy Pápáról „Isten kegyelmébül egészséges Helyből, ahol sem Cholera, sem más dögletes s ragadós nyavalya nincsen” Óbudára utazhasson „fogadott kocsin”, felesége „visszahozása végett”. Szalczer Ignác végül július 17-én, vasárnap kelt útra, és az útjába eső valamennyi település járványügyi főfelelőse bejegyezte, hogy ott volt. Még vasárnap eljutott az „epemirigytül mentes” Veszprémbe, Ösküre, Várpalotára, és hétfőn, 18-án megérkezett Székesfehérvárra. Áthaladt Pákozdon, Tétényben és Budán is. Abban az évben 19-én volt a Tisa beAv-i böjtnap, aznap nem utazott, és 20-án már újra Székesfehérváron volt, vagy voltak immár a feleségével együtt. A történet többi részét nem ismerjük, reméljük békésen és egészségesen hazaértek Pápára. Közben, pont ezekben a napokban Pesten néhány, a korlátozásokat túlzásnak érző polgár szétverte a várost. Utazó levél Szalczer Ignác részére, Veszprém, 1831. július 12. @MZsML 2021.63 Online adatbázisban Toronyi Zsuzsanna

Állandó kiállításunkban, a Múzeum keleti falán a Mizráh (kelet) – táblák között akad egy igencsak különleges szárnyasoltár (triptichon) formájú Mizráh-tábla. Ez is a keleti, vagyis jeruzsálemi irányt hivatott jelölni az imádkozók számára. A tábla közepén Mózes látható a tízparancsolat kettős kőtábláival, kihajtható szárnyain pedig a tízparancsolat táblái és a bibliai törzsek jelképei kis pajzsokon. A szokatlan, keresztény szárnyasoltárra emlékeztető formájú Mizráh táblát Tolnai Béla pesti tanár ajándékozta a múzeumnak 1933-ban. A tárgyat a múzeum dolgozói ismerték, hiszen a Múlt és Jövő című zsidó kulturális folyóirat 1912-ben illusztrációi között bemutatta, erre hivatkozva kérték a tanárt, hogy a „zsidó ipaművészet e remekét” ajándékozza a múzeumnak. A táblának másik példánya is ismert, a bécsi zsidó múzeum „Schaudepot” részlegében Tolnai Béla alkotásaként, 1910-es évekre datálva szerepel. A tábla feltehetően nem Tolnai Béla gyógypedagógus, az Országos Izraelita Siketnéma Intézet igazgatójának alkotása. A tárgy közepén lévő festményen szerepel egy alkotói aláírás, de egyelőre nem sikerült még azonosítanunk az alkotót. Akárki is készítette, ez a keleti irányt mutató tábla nagyon különleges. A zsidó múzeumok alapításának korszakában, az 1910-es években, a zsidó-keresztény testvériség, a hasonlóságok, a közös gyökerek bemutatása különösen fontos volt, ezért volt fontos ennek a keresztény szárnyasoltárra emlékeztető tárgynak a bemutatása. A szárnyasoltárok (triptichonok) kialakulása és virágkora a 14-15. századra tehető. A bezárt szárnyak az isteni titkokat, a nyitottak pedig a kinyilatkoztatást jelenítik meg. A tábla tetején és alján is egy-egy zsoltáridézetet olvashatunk: Felül, a Mizráh felirat mellett a 113. zsoltárból olvashatjuk: „Napkelettől napnyugtáig legyen dicsérve Isten magasztos neve.” Ugyanez az idézet látható a Dohány utcai zsinagóga tóraszekrény feletti részén is, héberül. A tábla alján a 92. zsoltár „Jó dolog dicsérni az Urat, és éneket mondani a te nevednek, oh Felséges!” szavait tüntették fel. A középső festményen az a jelent látható, amikor Mózes visszaérkezik a Szináj hegyről a tízparancsolat kettős kőtábláival. „És történt, hogy midőn leszállott Mózes a Szinaj hegyéről és a bizonyság két táblája Mózes kezében volt, midőn leszállott a hegyről: Mózes nem tudta, hogy sugárzott arcának bőre, mivel beszélt Vele.” (2Mózes 34:29) A Vulgataban, vagyis a latin-nyelvű Biblia-fordításban találunk egy fordítási hibát. Az eredeti szövegben a következő kifejezés olvasható: „kárán or pánáv” – vagyis „sugárzóan fénylett az arca bőre”. A „kárán” azt jelenti, hogy sugárzik, viszont a magánhangzók nélkül ugyanígy írt „keren” főnév sugarat is és szarvat is jelent. Tudjuk, hogy a héberben csak a mássalhangzókat jelöljük; más magánhangzókkal „ugyanaz” a szó más jelentést kaphat; ezért a „keren” „szarv”-ként való fordítása miatt („szarvak voltak a fején” – sőt, egyenesen az arcán) a keresztény Európában egészen a reneszánszig elterjedt Mózes szarvakkal való ábrázolása. Amikor kiderült, hogy fordítási hiba, volt, hogy ez ihletett meg művészeket, pl. Michelangelo-t. És persze ez a hiba és félrefordítás abban sem segített sokat, hogy a zsidók ördöggel való cimborálásának képzete ne terjedjen el. A táblán inkább, mint valami fénycsóvát láthatunk Mózes fején. Mikor lejött a Szináj hegyről, meglátta, hogy Áron segítségével a várakozó zsidók aranyborjút, vagyis bálványt készítettek, és dühében összetörte a két kőtáblát. Ezért történt tulajdonképpen kétszer a Tóraadás; Mózes ismét felment, és lehozta a(z újabb) kőtáblákat. Ezen a képen is, a szárnyakon is láthatjuk a tízparancsolatot, és a szárnyakon a 12 törzs jelképe is megjelenik. Mózes Ötödik könyvének 27. fejezete sorolja fel a törzseket: Simeon, Lévi, Júda, Isszachár, József, Benjamin, Ruben, Gád, Áser, Zebulun, Dán és Naftali. Bánfalvi-Orosz Eszter

Perlmutter Izsák: Parkban / A festő rákospalotai otthona, 1910. (olaj, vászon 64.2318) Pelrmutter Izsák Budapesten született tehetős, művészetkedvelő, nagypolgári zsidó családban. Apai nagyapja, Perlmutter Jakab több bérház tulajdonosa is volt, többek között a kőbányai sörházat tőle vette meg Dreher Antal 1862-ben. Pelrmutter Izsákot családja támogatta festői ambícióiban, édesapja amatőr festő volt, és az ő halála utána nagyapja, Jakab foglalkozott a képzésével. Budapesten először Magyar-Mannheimer Gusztáv oktatta, ekkor elsősorban szénrajzokat készített, majd Karlovszky Bertalan és Bihari Sándor közös iskolájában tanult immár festészetet. 1891-től megszakításokkal Párizsban élt, a Julian Akadémián folytatta tanulmányait. A francia fővárosban elsősorban Degas, Renoir és Manet hatott rá, és találkozott Munkácsy Mihállyal is. 1898 után Hollandiában telepedett le, először a larreni művésztelepen, majd Vollendamban. A Magyar Zsidó Múzeum és Levéltár gyűjteményében – a festő szinte minden korszakából – őrzött képei közül kitűnik két, Hollandiában készült festmény (Nyár Hollandiában, Utcarészlet Hollandiában), amelyek dekoratív felületei, erős színekkel, valőrökkel létrehozott fény és árnyék „foltjai” olyan fauve-ista festők felületkialakítási megoldásaihoz hasonlítanak, mint Ziffer Sándor vagy Perlrott Csaba Vilmos. Perlmutter ekkor sötét árnyalatokat és erős színeket használt képein, színei később kivilágosodtak. 1904-ben hazaköltözött; rövid ideig Besztercebányán, illetve a szolnoki művésztelepen dolgozott, tájképeket, csendéleteket, paraszti életképeket festett. 1908-tól Rákospalotán telepedett le feleségével és fogadott lányával. Itt készült művei közül, amelyek családját és otthonát, annak kertjét ábrázolják, többet is őriz a Magyar Zsidó Múzeum és Levéltár, így például az egyik, 1910-ben festett remekművét (Parkban / A festő rákospalotai otthona). A plein air kép szimmetriáját megbontja az előtérben látható kalapos lány (a festő nevelt lánya Reiszner Gizella, becenevén Cleo) figurája és a jobb alsó sarokban megfestett tárgyak együttese. Emiatt a képkivágás kifejezetten merésszé válik, szinte úgy érezzük, hogy felborulnak a perspektíva szabályai. A festmény központi eleme egyértelműen a kép szereplői fölé boruló fa árnyékát és a napsütötte felületeket elválasztó határvonal, az árnyékos és a napsütötte felületek ütközésének formai megoldása. A képen a fény teremti meg a formákat, amelyek azonban sem nem olvadnak kétdimenziós folttá, mint a fauve-oknál, sem nem válnak absztrakt foltokká, mint például Turner képein. A festményen a fény, az árnyék, valamint az alakok egyaránt anyagszerűek, egyik sem súlyosabb a másiknál, egyenrangú tényezők. A fény hangsúlyozása, a lokális színek tisztasága és anyagszerűsége, a visszaverődések (reflexek), a formaértelmezés, a felület szőnyegszerű jellege a magyar szecessziós festészet remekművévé teszik a festményt. Lázár Béla 1921-es monografikus írásában szenvedélyes hangon beszél Perlmutter kolorista festészetének kialakulásáról és jellegéről, amely szerinte Delacroix-hoz áll a legközelebb.[1] Hosszan elemzi, ahogyan Perlmutter, távolodva Monet-tól és az impresszionistáktól, rátalál saját stílusára. Lázár szerint ezt a stílust leginkább a fény, a szín és a forma viszonyának vizsgálatával lehet megragadni. Így fogalmaz: „Egy egész világ választja el a korai francia impresszionistáktól… Neki nem a köd vagy a vibráló napfény, nem a mozgás-illúziót adó apró színfolttömeg a piac képe. Ő megnézi – még az aprónak látott kofákban is – a mozgásban megnyilatkozó karaktereket, hatalmas színegységbe olvasztva a sok színelemet, hogy ilyképp egységhez: stílushoz jusson.” A festőnek a színhez és a fényhez fűződő viszonyát egy történettel eleveníti fel Lázár: „Egy délután – beszélte egyszer Perlmutter – egy egész hosszú délután plein air-t festettem a kertben. … Elöl egy sárga folt, abból indultam ki, s ahhoz tértem vissza. … Közelebb mentem, s láttam, hogy egy sárga kendő ... Vállat vontam ... Engem csak mint színérték érdekelt.” Perlmutter végrendeletében festményeit, villáját, valamint a ma a Terror Háza múzeumként működő Andrássy út 60. szám alatti bérpalotáját a zsidó hitközségre hagyta, azzal a kikötéssel, hogy zsidó múzeumot hozzanak létre benne, vagyona háromnegyed részét pedig idős, munkaképtelen művészek segítésére fordítsák. A végrendeletről a Magyar Zsidó Múzeum az 1932. december 26-án kelt irat szerint így emlékezik meg: „…Ezek után engedjék meg, hogy megemlékezzem Egyesületünk első és legnagyobb alapítójáról és jótevőjéről, a magyar művészet egyik legfényesebb csillagáról, Perlmutter Izsák festőművészről, ki egész életét a magyar művészetnek szentelve, halála után is tényező óhajtott lenni a magyar zsidóság kultúrájának továbbfejlesztésében. Ezen gondolat vezette őt azon nemes elhatározásában, hogy bizonyos előfeltételek bekövetkezte után, vagyona a magyar–zsidó tudomány és művészet érdekeit és céljait szolgálja. … Nem kell mondanom, hogy mit jelent ez egy oly intézmény részére, mely nem pénzügyi alapokon lett felépítve, hanem a magyar zsidóság kulturális és történeti emlékei iránti áldozatkészségből akarja létfeltételeit biztosítani.” [2] [1] Lázár Béla: Perlmutter Izsák. Budapest, Légrády Testvérek, 1921 (a szöveg címe is innen származó idézet). [2] Magyarországi Izraeliták Országos Irodája iratai. Igazgatósági jelentés. Előterjesztette Dr. Munkácsi Ernő titkár, a Múzeumegyesület 1934. évi június hó 29–án tartott közgyűlésen. In: IMIT Évkönyv (1934): 352–358. Farkas Zsófia

|

Categories

All

Archives

September 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed